Why Name Calling Doesn’t Work, and How to Have More Effective Conversations

We have a staunch “No Name Calling” position at Sexvangelicals.

In this blog post, we will explore how the cycle of name-calling occurs in relational spaces, as well as on a political and systemic level.

In a relationship dynamic, name calling—using a putdown to describe something the other person is doing, starting a sentence with “You’re ___”, or a combination of the two—leaves the other person with two options.

Shut down. This ends the conversation; however, the receiver is left holding onto whatever insult was thrown out, and the relationship is unable to process what just happened.

Fight back. This typically continues the conversation, often in a highly emotional format.

As psychotherapists, we notice that the diagnostic lexicon of the DSM-V and ICD-10 gets injected into the name calling process. For example, the diagnostic process inherently labels (or name-calls) clients by reducing them to their diagnosis. Ten years ago a therapist told me (Julia) that I had “every sexual dysfunction in the DSM” and that I was “just an obvisouly anxious person” based on the criteria that the DSM provides for “disorders” of all kinds.

Ouch. This is not a particularly humane process enacted by the “helping profession”.

Furthermore, as sex therapists, we notice that the vernacular of the social justice warrior Bible also gets injected into the same problematic process. Although progressive communities often give lip service to treating individuals and groups with kindness (i.e. no name calling), they, in fact, name call under the guise of social justice advocacy. We would argue that this does not actually promote social justice.

This often manifests by reducing complex issues to simplistic blaming. “Well, you’re just sexist… you’re a privileged white male using your white/hetero privilege… look at you and your white woman tears.”

To be clear: We need to talk about all this. We need to combat the ways that racism, sexism, homophobia, etc. impacts and devastates our families and communities. But, name calling without actually defining what we mean, does not move us toward progress. Liberal groups are experts at using buzz words (like decolonize) without defining terms or engaging in a focused dialogue. Let’s get specific with two examples below.

Example 1. If I say, “You’re racist” and leave it at that, the person I’m speaking with either gets angry (on a national level, this is how White Republicans typically answer) or enters into some sort of shame spiral (commonly how White Liberals respond to the scarlet R).

Whether I’m justified in calling someone racist is not relevant. The dialogue either shuts down or spins out of control.

However, if I say, as I did yesterday in a conversation with a colleague about diversity, equity, and inclusion, “It’s a racist process to expect people of color to provide continuing education about diversity because it puts the onus of awareness building on those communities , and historically speaking, White spaces don’t listen particularly well to communities of color,” then my colleague and I can have a dialogue that addresses how we might collaboratively address the complexities of the process of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Our rule: If we’re going to use name-calling, we need be able to describe the process that reinforces the descriptor, with minimal usage of the word “You”. The conversation then becomes about the process, rather than the character of the other person.

Failure to do so creates an ineffective dialogue.

Example 2. Donald Trump is a narcissist.

This is the genius recipe of Donald Trump (and the Republican Party):

Put a Falstaffian character who swears a lot at the head of the organization.

Watch the rest of the nation, especially the Democratic Party, engage in comments like “You’re a narcissist.”

The name-calling spreads like a wildfire, so that everyone who votes for Trump is also “narcissistic”.

The conservative media and public relations teams within the Republican Party uses the name-calling as bulletin board material to reinforce the narrative that White people are the victims here, not people of color.

The sense of victimhood unifies the Republican base around a more reactive, extreme set of policies.

Repeat steps 2-5 so much so that the Republican Party handcuffs the process of policy making through their interest in preserving the identity of a White Christian America than the do creating policies that protect the entirety of the nation.

What if we tried something different?

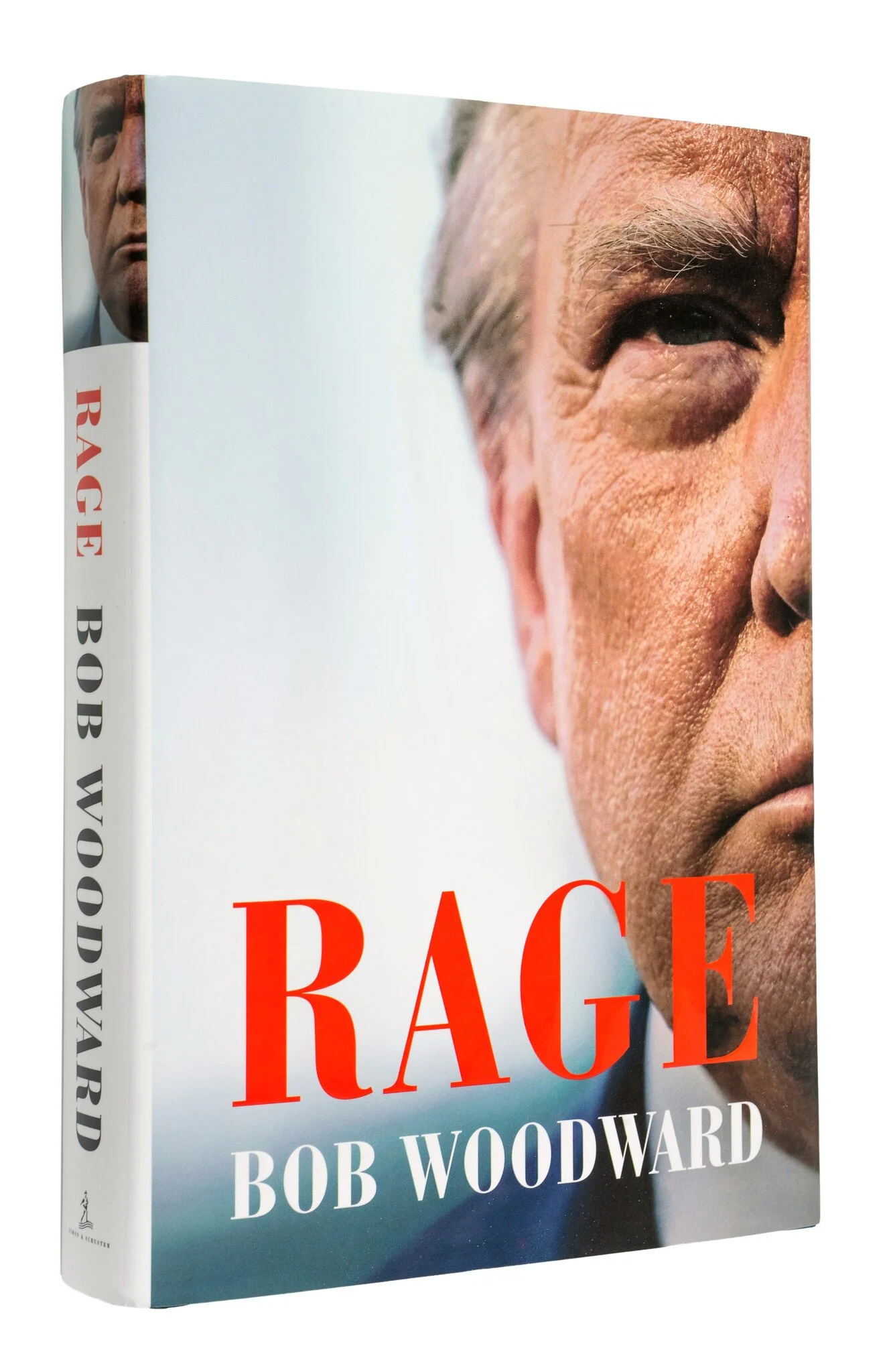

I’m reading Rage by Bob Woodward. Woodward, an associate editor at the Washington Post, is given permission to write about the Trump administration. The first half of the book describes the relationships between Trump and his initial cabinet, especially the experiences of Rex Tillerson, the original Trumpian Secretary of State, and Jim Mattis, the original Trumpian Secretary of Defense. (Remember them?) The second half of the book details the Trump administration’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak.

TL;DR: The Trump administration did not do a good job responding to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Trump agrees to have fifteen interviews recorded for this book, many of which Woodward writes the dialogue for in the book.

In Chapter 28, Woodward depicts a conversation where he talks about Trump’s utilization of Voldomyr Zelenskyy to get more information about Joe and Hunter Biden, asking, “Would you want the president of the US to be talking to foreign leaders about investigating anyone?” (In retrospect, screwing with Zelenskyy is bad policy, but that’s another conversation.)

Over the next few pages, Trump talks about his definition of corruption, the narrative that the US is funding the rest of the world in fighting corruption, the role of Ukraine in present-day Europe, and the disappearing of whistleblowers.

Trump’s inability to stay on topic is a common way to spoof the former President; James Austin Johnson nails this dialogical process, and the SNL cast captures every emotional response you can imagine, from confusion and befuddlement to assimilation (follow Trump wherever he goes) and outright anger. We laugh along, because if we didn’t, we would be screaming our lungs out around how infuriating it is to be in a relationship with someone who consistently shifts the topic.

We can call this narcissism. We can call this ADHD. The diagnosis is irrelevant. Trump’s (and for that matter, the Fox News reporters’) inability/unwillingness to stay on topic gives him power in conversations, especially when journalists attempt to track Trump’s rhetorical movement and the conservative media combines this process with the above described Genius Recipe of Donald Trump.

Woodward does something different. He makes Trump stay on topic. Sometimes Trump goes on a bewildering tangent. Sometimes Trump uses anger to shut down the conversation, denies what Woodward is saying with some variation of “Fake news”, or walks away. Woodward doesn’t lose his original question, repeating it until Trump answers the question. In this case, he answers Woodward’s question as “Yes, the President does have power to investigate corruption of foreign leaders,” which has its own dangerous consequences.

Name-calling Trump and the people who vote for him have only further divided an already divided nation. However, if we can name the process of, say, switching topics incessantly as a way of avoiding uncomfortable conversations about the intersection of policy and identity, we will likely have different conversations.

I cannot imagine how exhausting these conversations were for Woodward; as a couples therapist, sessions with a couple who quickly switch topics involve a lot of energy. However, Woodward provides us with some tips for navigating a dialogue with someone who avoids by switching topics.

A clear understanding of what you want to accomplish, and an unwavering dedication to have your perspective heard.

Comfort around conflict, knowing that a person may use a variety of emotional strategies and manipulation to avoid self-reflection.

A process for slowing down the pace of the conversation, which means slowing down your own cardiovascular system.

A short, simple explanation and description for the position that you hold, one that describes relational process, as opposed to characterological flaws.

We hope this perspective helps you have more effective dialogue!